Synopsis

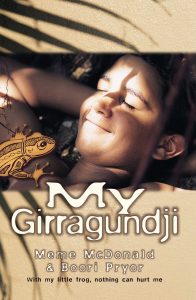

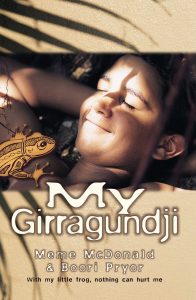

Cover of My Girragundji, written by Meme McDonald and Boori Monty Pryor in 1998

My Girragundji is an 84-page novel written by Meme McDonald and Boori Monty Pryor (McDonald & Pryor, 1998). It tells the story of how a young Aboriginal boy overcomes his fears of visits from the hairyman at night, of approaching his first girl friend Sharyn, of migaloos (white people), and of dealing with the bullies at school. In the course of the story, the boy develops a special relationship with a little tree frog called Girragundji that helps him connect to his Aboriginal ancestors and to build a positive sense of self

Boori Monty Pryor was the Australian Children’s Laureate during 2012-13, along with Alison Lester. Meme McDonald is a founding member and stage director of the WEST Theatre Company, children’s book author and recipient of the 2012 Ros Bower Award for an outstanding, life-long contribution to community arts and cultural development.

The book trailer above includes paragraphs that describe the first encounter between the first-person narrator and the frog in what is the central transition between paralysis and courage.

Selection criteria and Australian Curriculum connections

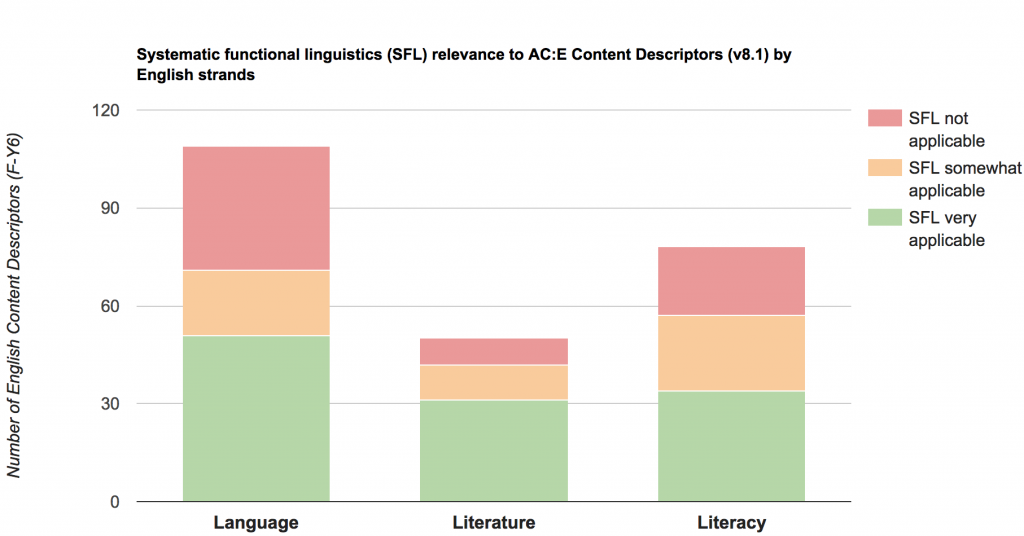

In the Australian Curriculum (AC), Literature is one of three inter-related developmental sequences or ‘strands’, together with Language and Literacy. The explicit aim of the Literature strand is to provide students with “access [to] a broad range of literary texts and develop an informed appreciation of literature” (National Curriculum Board, 2009, p.5). In the latest iteration of the AC v8.2, the Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority (ACARA) describes quality literature as satisfying some of the following criteria and enduring values (ACARA, 2016a):

- Artistic value

- Personal value

- Social value

- Cultural value

- Aesthetic value

- Attract contemporary attention

- Potential for enriching students’ lives and expanding scope of experience

- Represent effective and interesting features of form and style

These criteria are developed in further detail in the literature companion for teachers published by the Primary English Teaching Association Australia (PEETA) (McDonald & Walsh, 2013).

Enduring artistic value can be defined as the quality that writers develop in their work and how this resonates with readers over time (e.g. Walmsley, 2012). My Girragundji is a popular book with young Australian readers and has recently been turned into a stage play and film script (McDonald, 2013).

Personal values relate to personal resonance, emotional connections, empathy and inspiration developed in the reader by reading a book (e.g. Carnwath & Brown, 2014). Students are likely to be drawn into the first-hand narrative of the boy and main character in My Girrragundji and empathise with his challenges. Students might also become inspired by the idea of developing strength from a relationship with a pet or totem.

Social values relate to social benefits such as civic engagement. The Melbourne Declaration on Educational Goals for Young Australians states the imperative for all young Australians to become active and informed citizens and to develop reconciliation between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians (Barr et al., 2008). The cross-curriculum priority (CCP) Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander histories and cultures (ACARA, 2016b) applies this contemporary goal by placing attention on advocating and teaching Indigenous perspectives and understanding for all students to engage in reconciliation. In My Girragundji, some passages directly address reconciliation, such as “That’s our special place where the river meets the sea. It’s their place really, my Aunty Joyce and Uncle Arthur’s place. But they reckon it’s our place, and Dad doesn’t argue with that ‘cause he reckons that’s right. They’re white and we’re black and I don’t know whose place the Bohle is, it just is, and they’ll always be our aunty and uncle.” (McDonald & Pryor, 1998, p.43-44). In 2012, Pryor was made the inaugural Australian Children’s Laureate for his stories that “[…] create positive visions of the future for both Indigenous and all Australians” (Australian Children’s Literature Alliance, 2016).

Cultural values relate to the process of producing and negotiating value between different cultural organisations and expressions (Carnwath & Brown, 2014; Agha, 2003). Inclusive teachers must make an effort to embrace diversity and include literature that portrays the full range of ethnicities, cultures, languages/dialects, religions, family structures and socioeconomic statuses within the classroom (Boyd et al. 2015; Harrison, 2016). My Girragundji provides an authentic contemporary window into a socioeconomically disadvantaged Indigenous community, describing the challenges and demands on an age peer in an engaging and at times humorous way that will expand the scope of experience for many mainstream class students. In the face of adversity, the first-person narrator develops resilience and a proud sense of self, based on connection to country and culture. The book provides insight into local Aboriginal culture and helps to build empathy, recognition and support for Indigenous students from similar background in the class. For Indigenous students, My Girragundji can express and reinforce cultural identity and a pride in Aboriginal English, thereby enriching all students’ lives.

Aesthetic value has been described as the “benign capacity” of quality literature to be experienced and appreciated as something cohesive, harmonious in form, content and symbology, and as a capacity to emotionally move the reader (Beardsley, 1981, p.240). My Girragundji is emotionally engaging, the language original and fresh, with photos and illustrations of high standard. The creative use of fonts and Aboriginal English, including terms such as jalbu (young woman or girl), migaloo (white-skinned person), wirrell (shell fish for eating), creates a text with many effective and interesting features of form and style.

The English curriculum advice for every year level is to work with a range of literary texts, including “Australian literature, […] oral narrative traditions of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples, as well as the contemporary literature of these two cultural groups, […]” (ACARA, 2016c). The State of Queensland, Queensland Curriculum and Assessment Authority (QCCA) provides additional guidelines for embedding Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander perspectives in schools, recommending five criteria for evaluating the quality of a teaching and learning resource (QCCA, 2010):

- Authenticity

- Balanced nature of the presentation

- Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander participation

- Accuracy and support

- Exclusion of content of a secret or sacred nature

My Girragundji is an authentic text, co-authored by Indigenous writer Boori Monty Pryor. Pryor was awarded the Promotion of Indigenous Culture award from the National Aboriginal Islander Observance Committee in 1993. The story is written in the first-narrator perspective of an unnamed ten or eleven year old Aboriginal boy, closely modelled on Pryor’s childhood memories. It can therefore be considered accurate and balanced in nature of the presentation, illustrating contemporary non-‘exotic’ aspects of Indigenous culture and perspectives other than representations of male adults. By concluding in a chapter ‘How My Girragundji was written’, the authors acknowledge the participation of the Yarrabah community. The acknowledgements make it explicit that the local community was actively involved in taking photographs and reviewing the story, guaranteeing that no content of a secret or sacred nature was included. My Girragundji specifically addresses the CCP organising ideas OI.2, OI.5 and OI.6 (ACARA, 2016b) and focuses on Indigenous perspectives such as ways of valuing, being, doing and knowing, as opposed to potentially problematic indigenised content (Lowe & Yunkaporta, 2013).

The topic and language of the book, as well as the similar age of the main character make My Girragundji most suitable to Years 5 and 6 students. A strong link to the year-level English curriculum description is evident, as readers are to explore a range of non-stereotypical characters and texts including junior and early adolescent novels that explore “themes of interpersonal relationships and ethical dilemmas within real-world and fantasy settings” (ACARA. 2016c).

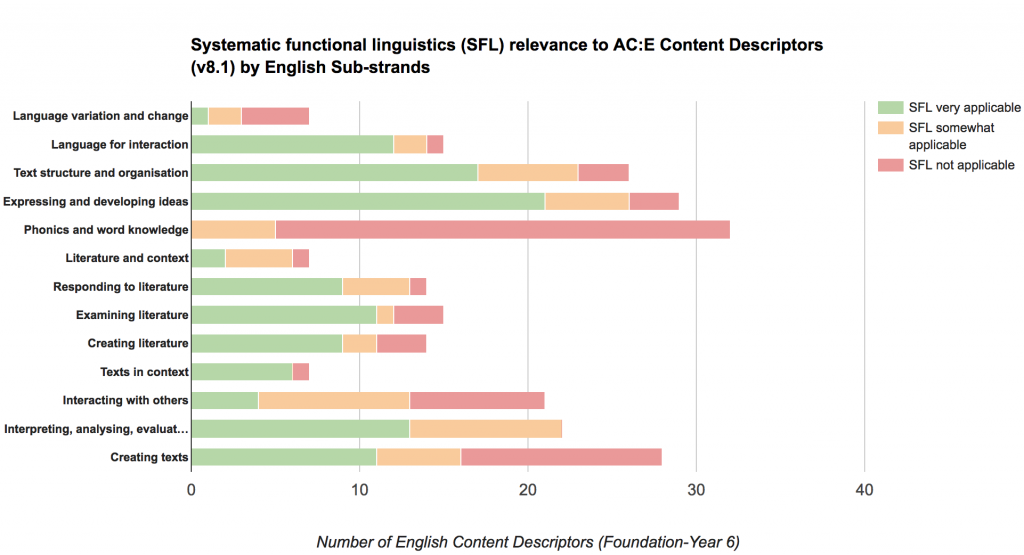

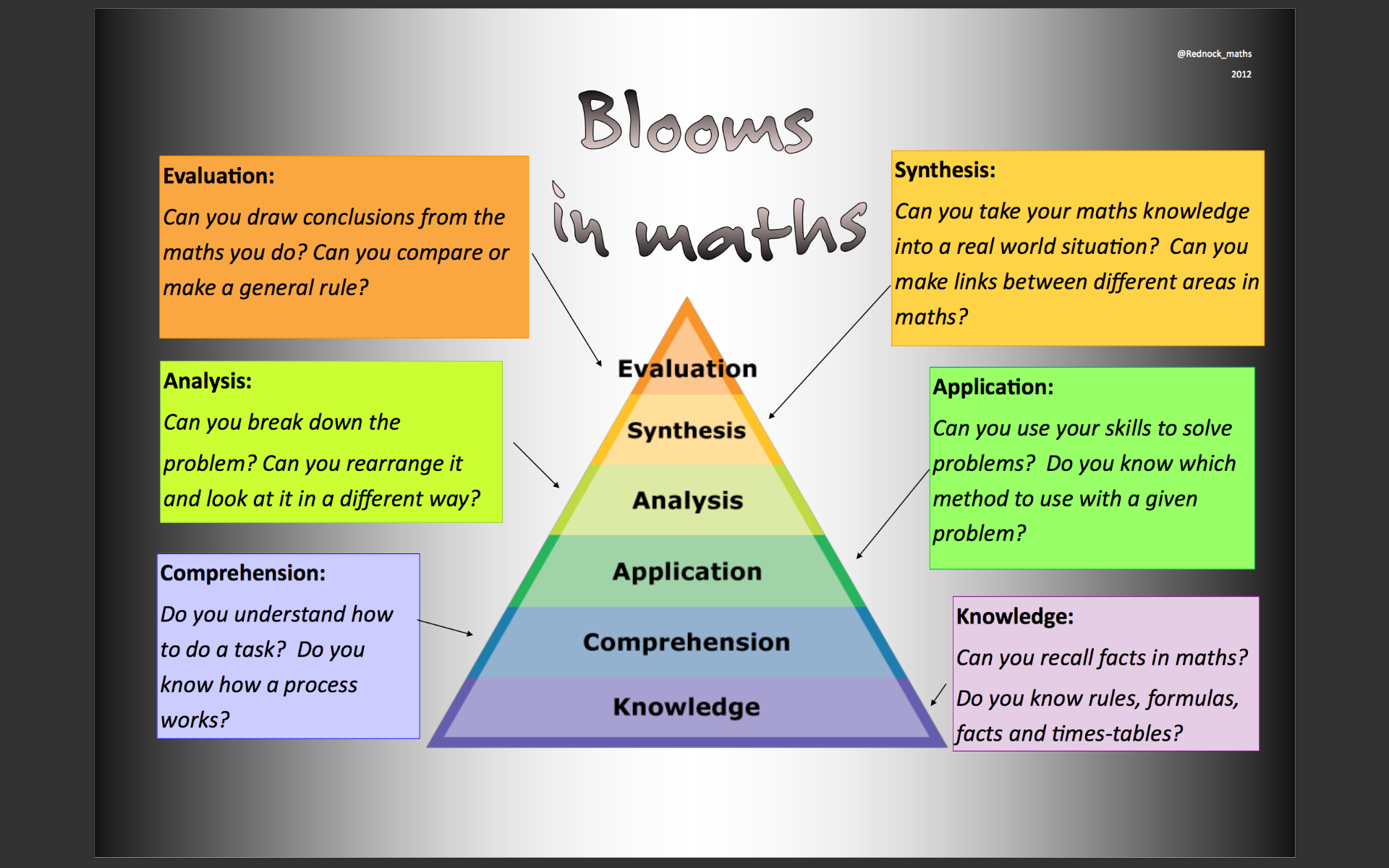

In Year 5, the most applicable CD from the Literature strand in ‘responding to literature’ is ACELT1609 “present a point of view about particular literary texts using appropriate metalanguage, and reflecting on the viewpoints of others”. The students could reflect on Indigenous viewpoints, experiences and opinions expressed in the book, possibly in a format where they are required to create their own text on a hairyman exploring what keeps them awake at night. Alternatively, students could develop a script for a stage play on episodes of the book presenting one or more perspectives of themes in the book such as growing up, family conflict, friendship, bullying and spirituality (see also link to Literacy CD in ‘creating text’ ACELY1714) (ACARA, 2016).

In Year 6, the most applicable CD from the Literature strand in ‘literature and context’ is ACELT1613 “make connections between students’ own experiences and those of characters and events represented in texts drawn from different historical, social and cultural contexts”. This CD can be applied to build the field knowledge on contemporary Indigenous communities at the beginning of the unit. The ‘responding to literature’ CD ACELT1615 “identify and explain how choices in language, for example modality, emphasis, repetition and metaphor, influence personal response to different texts” is well suited to engage students with the unique style of writing and Aboriginal English, followed up by a closer examination and analysis using ‘examining literature’ CD ACELT1617 “identify the relationship between words, sounds, imagery and language patterns in narratives and poetry such as ballads, limericks and free verse”. Students could extract sad and funny passages from the book and discuss how the authors play with language features to achieve particular purposes and effects (see also link to Language CD in ‘text structure and organisation’ ACELA1518) (ACARA, 2016).

Current debates about the use of quality literature in Australian classrooms

The Australian Curriculum only defines types of texts that need to be studied from Foundation to Year 10 and provides the set of criteria discussed above on what quality literature looks like. The English curriculum recommendations further highlight the importance of incorporating Australian literature, including oral narrative traditions and contemporary literature of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, as well as classic and contemporary world literature, in particular texts from and about Asia. As for what makes and who selects the best literature for schools, three debates are particular pertinent to the current situation in Australia:

- The extent to which the English curriculum is balanced or distorted by emphasising Indigenous Australian and world literature, and the value of a classical Western literature canon for Australian students

- The competition between teachers, schools, states, and commercial publishing houses for the authority to choose classroom literature

- The value of print-based literature versus digital media and its impact on reading

In the 2014 review of the Australian Curriculum by the Australian Government, Department of Education and Training (DET), a number of reviewers such as the Institute of Public Affairs objected to the emphasis on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples’ literature and its literary heritage, calling for a greater focus on Western literature in the English classroom, (DET, 2014a; Riddle & Honana, 2014, Forrest & Schodde, 2014). This view was supported by specialist consultant Spurr, appointed to make recommendations to the federal government’s review of the national English curriculum. Spurr remarked that “[…] in the three points on which all curriculum subjects must be focused – Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island peoples; the Asian region, and sustainability – mandating priorities that could be a distraction from the core work of the curriculum, bearing no direct relation to the educational and disciplinary purposes that the curriculum for the study of literature in English is designed to facilitate and fulfil. ” (DET, 2014b, p.4). Spurr has since resigned from his professoral post following the exposure of a series of personal inflammatory emails that included derogatory references to Aboriginals, Asians and women casting doubt on the integrity of the review (Alcorn, 2014). On the other side of the debate, the Australian Association for the Teaching of English (AATE) supports the CCPs as important issues that need to be addressed in a national school curriculum at this point in the Australian history (AATE, 2014). This view coincides with a progressive understanding of the role of education in a pluralistic society, which affirms students’ understanding of their home and community cultures while helping them to participate in today’s multi-cultural and globalised world (Banks, 2013).

Closely related to the debate on English literature versus world literature is the question about the nature and value of teaching a classic literary canon, and the role that new literature and media should play in the classroom. Kevin Donnelly, the conservative education critic appointed to co-head the 2014 Australian curriculum review, strongly advocates Harald Bloom’s concept of a Western literature canon. He is of the opinion that English as a subject should focus on “enduring literary works that are part of the Western tradition” including “seminal authors such as Shakespeare, Swift, Dickens, Austen, Orwell, Lawson or Malouf”, as opposed to the AC “exploding the definition of literature to include “multi-modal texts”, and suggesting that students should spend time studying “tween mags, avatars, social networking and manga”” (Donnelly, 2010). Harald Bloom’s concept of a Western canon (Bloom, 1994) had sparked “canon wars” in the late ‘80s in which traditionalists advocated a curriculum focusing on classic works of predominantly British literature, while progressive academics promoted teaching an expanding body of works and a focus on modes of inquiry and interpretation (Donadio, 2007). In reference to the current “literacy war” in Australia, Ilana Snyder describes the position of teachers that argue for a dynamic repertoire of literature, reflecting the rapid changes in our society and world of ideas (Snyder, 2008). This position is supported by the AATE, who advocate that until Year 10 individual schools are in the best position to implement the curriculum with texts that their English teachers assess as most suitable for particular classes and communities. AATE explicitly rejects the idea of a literature canon stating “[…] we consider it would be inappropriate for any specific texts to be mandated for use” (AATE, 2014).

The idea that teachers choose the most appropriate texts can however be undermined by a more prescriptive implementation of the AC at state land school levels, and by schools buying into commercial reading programs. In Queensland, the DET provides state schools with comprehensive electronic curriculum planning and resource materials, referred to as Curriculum into the Classroom or C2C. The English C2C units include digital and print-based texts as teacher resources and classroom sets (DET, 2015). While DET explicitly states that it supports schools in applying flexibility to “adopt or adapt the materials to suit the learning needs of their students and local contexts” (2015), its sample teaching episodes are often implemented with minimal modifications. The C2C writers therefore are in a powerful position to promote particular works of literature. Many schools purchase a core reading program, conveniently packaged as sets of identical books for students, including a teacher’s edition of the book with worksheets and assessment tasks. Some literacy teachers are favourable of basal reader programs, suggesting that these schemes provide a convenient backbone for their lesson planning and free time up to provide better differentiation, including the provision of supplemental reading for more advanced readers (Reisboard & Jay, 2013). On the other side, many academics and educators point out that commercial reading programs have a number of limitations compared to teacher-selected quality literature. These include that the textbooks are often repetitive, less engaging, fail to build on prior student knowledge and do not develop metacognitive thinking (Dewitz & Jones, 2013).

Reading programs are increasingly integrating children’s books with digital multi-media content for computers and iPads, such as the Reading Eggs products (ABC Reading Eggs, 2016). Recent research suggests that in particular struggling readers are more likely to engage in reading on digital platforms that can support their reading experience with rich features, such as multi-modal content, interactive navigation, animated images and adaptable font sizes (Hughes, 2013). Teachers that like to curate their own quality literature for digital devices can face a number of technical challenges and limitations, such as a more limited range of digital children books and small screens (e.g. Mardis & Everhart, 2013).

While literacy teachers are navigating shifting policy directions and experimenting with the promises and limitations of engaging students in digital texts and reading apps (Hutchison et al., 2012), it is perhaps instructive to highlight one aspect of quality literature which is not explicitly stated in the AC criteria and often missing in the public debate: reading enjoyment. By selecting literature that is interesting, relevant and moderately challenging, students are most likely to engage in reading and develop an intrinsic reading motivation (Gambrell, 2015). If reading enjoyment is one of the strongest predictor for educational success (Kucirkova, Littleton, Cremin, 2015; Clark & De Zoysa, 2011), debates on classroom literature canons and formats, should perhaps be placed into the hands of the students, coached by their teachers and the school librarian (Strauss, 2014).

References:

Continue reading →

Loading...

Loading...