In 2008, the Australian Education Ministers declared a principal educational goal for young Australians is to be successful learners by developing “. . . the essential skills in literacy and numeracy and [becoming] creative and productive users of technology, [. . .], as a foundation for success in all learning areas” (Barr et al., 2008, p. 8). Consequently, the national English syllabus (AC:E) designed by the Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority (ACARA) defines literacy as “. . . the ability to read, view, listen to, speak, write and create texts for learning and communicating in and out of school” (ACARA, 2017a). These six receptive and productive language macroskills (Barrot, 2016) are emphasised across all key learning areas (KLA) with the general capability ‘Literacy’ as interrelated elements essential for comprehending and composing texts (ACARA, 2017b). The AC:E further draws attention to the social and multimodal nature of language learning (ACARA, 2017a). Consequently, the demands on twenty-first century literacy teaching and learning resources are different to those developed for the twentieth century industrial model of schooling (e.g. Seely Flint, Kitson, Lowe, & Shaw, 2014). Here, the educational app ‘Book Creator for iPad’ (Red Jumper Ltd., 2017a) is critically reviewed in context of the AC:E from multiple perspectives, including literacy development theories, language macroskills, the six guiding principles for teaching reading and writing in the twenty-first century (Seely Flint et al., 2014), and the four-resources model of reading (Luke & Freebody, 1997) as applied to multimodal texts (Serafini, 2012) and creative writing (Heffernan, Lewison, & Henkin, 2003). The author concludes that Book Creator for iPad is versatile and age-appropriate literacy resource that can be employed to teach and learn critical and multiliteracies in Australian primary schools, across KLAs including English.

Resource description

Book Creator educational app

Book Creator is a best-selling educational software running on Windows, iOS and Android platforms, with a browser extension in development (Kemp, 2017). It was launched in 2011, with the current release version 5.0.2 available on the iTunes app store for iOS 9 and above. The iOS app is priced at AU$ 7.99 per licence, with a 50% discount offered for schools through the Apple’s Volume Purchase Programme (Red Jumper Ltd., 2017a).

Book Creator supported media formats

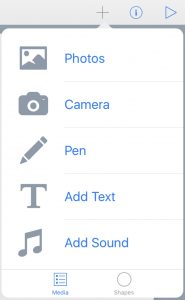

The Book Creator app is designed for school-aged children to create and publish multimodal ebooks. The core functionality includes widgets that allow adding text, images, drawings, shapes, audio and video to virtual book pages. Individual pages and final ebooks can be read out aloud, supporting twenty-seven languages, including thirteen English speaking voices and four Australia dialects. In reading mode, spoken words can optionally be highlighted and the speech rate adjusted. Book Creator supports publishing ebooks in multiple formats, including ePub, PDF and as as a video file with spoken text. Ebooks can be saved locally, or in the cloud (e.g iCloud, Dropbox, Google Drive) to support access-controlled sharing of student work with parents and school community. Alternatively, ebooks can be locally shared in the classroom using the AirDrop iPad functionality. As a result, Book Creator supports distributed content creation, where multiple students can work collaboratively on individual chapters that can be combined at a later stage (Hallett, 2013).

Critical evaluation and discussion

Most educational literacy software is designed with a narrow focus on developing and practicing particular skills such as phonemic awareness (e.g. Oz Phonics (DSP Learning Pty LTd., 2015)), sight words and spelling (e.g. Reading Eggs, (Blake eLearning, 2016)). In contrast, Book Creator is designed to be open-ended and to be used in creative ways across various KLAs to support the development of critical and productive multiliteracies. The developers of Book Creator value creativity, collaboration, cross-curricular integration, and “app-smashing”, i.e. the ability to seamlessly integrate other apps as part of the workflow (Red Jumper Ltd., 2017b). The company also prioritises dialogue with educators by offering free webinars and comprehensive customer support.

Book Creator excels as a top-down literacy development resource. The core intention of the app is to support students in creating ebooks. Multimodal ebooks are a whole-language product. Book Creator supports socially-situated learning through purposeful collaboration and dialogue, editing, and publishing. The app can be used in inquiry-based teaching and learning across all KLAs, for example in activities involving journaling and reflection. Perhaps the greatest value as a literacy resource is the ease-of-use with which all receptive and productive language macroskills (Barrot, 2016) can be meaningfully and seamlessly integrated into a single authentic product. Books are not just written but created, by seamlessly integrating text with images, audio and video recordings. The productive language skills are even expanded into the often neglected aspect of publishing for audiences (Jaakkola, 2015). The student experience between reading, listening (or being read to), and viewing the story as a movie is fluent. The app can be used to explore intertextuality, the links between different texts, personal experiences and outside knowledge. The students are invited to construct meaning by linking multimodal sources and developing the three schema-building connections: text-to-text, text-to-self, and text-to-world (Fountas & Pinnell, 2006).

The app can also be employed for critical literacy development. For example, Book Creator can be used to construct comic books with social justice themes (Stone, 2017), perhaps making use of speech and thought bubbles to explore multiple perspectives.

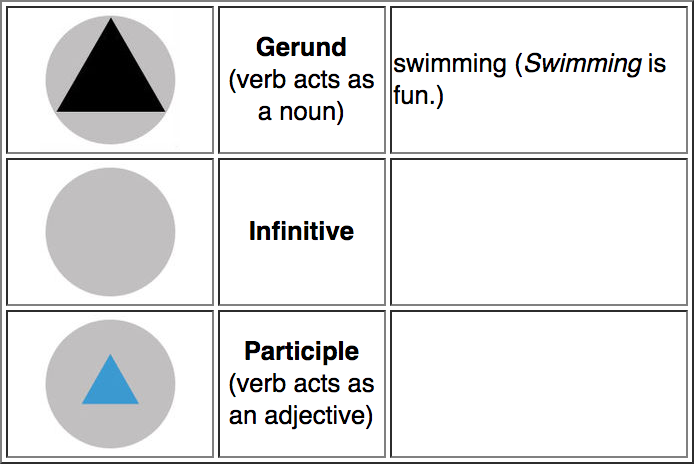

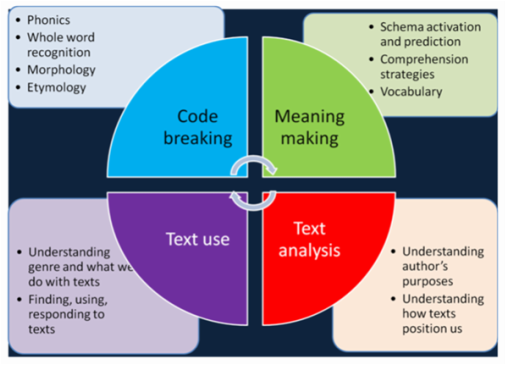

Basic Book Creator shapes

With the ability to publish in ePub and video formats, Book Creator lends itself as a tool to express opinions and take social action. The four-resources model (Luke & Freebody, 1997) is perhaps the most widespread model based on critical literacy theory in Australian schools. Originally developed by Peter Freebody (1992), it emphasises the socio-cultural practices and four interrelated essential roles of the reader: (1) decoding text as a ‘code-breaker’; (2) making semantic meaning as a ‘text-participant’; (3) making functional meaning as a ‘text-user’; and finally (4) critically analysing the text. This model is aligned with the four language cueing systems (graphophonic, semantic, syntactic, pragmatic) of the whole-language approach (Seely Flint et al., 2014). Frank Serafini (2012) expanded the original print-based model to address multiliteracies. Accordingly, the literate reader-viewer of multimodal texts acts as a :(1) ‘navigator’; (2) ‘interpreter’; (3) ‘designer’, and; (4) ‘interrogator’. Book Creator is designed to develop all four interrelated skills, with a particular focus on productive language skills. Lee Heffernan and co-authors adapted the four-resources model of reading to a four-resources model of writing in a primary school context (Heffernan et al., 2003). This model is used to support students in better communicating ideas, improving text composition, drawing on background experiences to construct meaning, and becoming more explicit and reflective in the representations and positions argued in the text. The simplicity with which students can add their voices (i.e. record audio) and perspectives (i.e. record photos and videos) makes Book Creator a great tool to develop critical and creative writing that addresses all four resources.

Ultimately, Book Creator as literacy resource is not limited to any particular theory of literacy development. Some creative teachers have used the app to support bottom-up literacy development through activities such as multimodal vocabulary practice (e.g. Dodds, 2015).

Another approach towards evaluating Book Creator as literacy resource is to critically assess ways in which this app can be used to address the six guiding principles for teaching reading and writing in the twenty-first century (Seely Flint et al., 2014):

1) Literacy practices are socially and culturally constructed. Book Creator encourages social interaction by offering multiple ways of collaboration between students, teacher, parents and the school community (Hallett, 2013). Cultural and linguistic diversity in the classroom is supported by offering few limits in terms of languages and genre conventions. However, the default page flow from left to right does not support languages that use right-to-left scripts, such as Arabic or Urdu.

2) Literacy practices are purposeful. Writing and publishing books is a purposeful form of literacy practice, in particular if the task design is inclusive and responsive to the students’ lives, and encourages cross-disciplinary learning. The simplicity with which text can be integrated with photos, audio and video recordings provides numerous opportunities for students to express themselves, organise and document their learning through journaling, support design thinking and prototyping (Holland, 2017), even playing interactive learning games (Dodds, 2015). The app can be used to support and complementing reading activities, for example by creating audiobooks of class readers. The sharing and publishing functionality offers opportunities to create ebooks for both enjoyment and assessment.

3) Literacy practices contain ideologies and values. Book Creator supports a range of literacy practices in virtually limitless social and cultural contexts. On the iPad, the app is portable and can even be used outdoors in nature for many hours. Shapes, such as speech and thought bubbles superimposed on images, can be used to communicate perspectives (Baker, 2015) and allow individual book characters to speak and think for themselves, perhaps juxtaposed on facing pages.

4) Literacy practices are learned through inquiry. The starting point of a new Book Creator project is a blank canvas, which can be customised. All content needs to be developed, the ideal starting point for student inquiries. The app is explicitly designed to support students in the drafting, composing and publishing processes. At each stage, students can work individually or in groups, and share their work for discussions, assessment and reflection (Vasinda, Kander, & Redmond-Sanogo, 2015).

5) Literacy practices invite readers and writers to use their background knowledge and cultural understandings to make sense of texts. Book Creator supports multiple ability levels and prior experiences with texts through inbuilt scaffolding tools such as the read-aloud function. Options to adjust the speed and dialect of the voice, and the ability to highlight spoken words make this app a powerful tool for supporting students struggling with unfamiliar aspects and practices around literacy development, e.g. EAL/D students. Emerging writers will enjoy the ability to creatively express themselves through multiple media to complement their writing (Rowe & Miller, 2016).

6) Literacy practices expand to include everyday texts and multimodal texts. Book Creator supports any type of genre and register, and can complement literacy practices across multiple contexts and KLAs. Multimodal texts are the core function of the app, supporting written, visual, auditory and spatial modes in any possible combination.

While all this demonstrates that Book Creator can be applied to a wide range of literacy teaching and learning scenarios, one fundamental question remains: to what extent does the app transform literacy learning compared to traditional, non-technological alternatives such as scrapbooking? A practical framework to critically evaluate educational technology and software is the SAMR model by Ruben Puentedura (Romrell, Kidder, & Wood, 2014).

Accordingly, Book Creator is reviewed in terms of its ability to Substitute, Augment, Modify and Redefine literacy learning experiences compared to traditional scrapbooking. The answer to the question above depends on how the teacher and students are employing the app. Book Creator can be used to simply substitute paper-based story writing through activities that are limited to individual writing exercises, perhaps allowing students to include pre-selected images. However, once students make use of the camera and microphone on their iPads to include spoken words, photos and videos, Book Creator will augment scrapbooking by functionally improving the possibilities. In order to modify the traditional resource, the app will need to be used in unprecedented and novel ways. This is for example the case in the area of collaboration. Book Creator enables easy duplication and sharing of documents, instant contextual feedback through annotations, and process documentation for assessment (e.g. Sample, 2014). Finally, traditional scrapbooking is only truly redefined when the app is used in ways inconceivable without technology. Arguably, workflow integration between Book Creator, other apps and cloud services is the area that establishes Book Creator as a transformative literacy resource. Examples include the ability to import any student-generated content, such as stop-motion movies, student images in front of a customisable backgrounds, and the novel ways that content can be shared and published to reach new audiences (Sample, 2014).

Book Creator comes with a price tag. Although reasonable in comparison to other educational resources and technology, it will require a purchase plan that can limit its appeal for teachers that plan to use the app only for a single project. The software is also limited in terms of editing images, audio and video. Advanced editing functionality will require integration with other apps that often need to be downloaded. Other useful functionality, such as the ability to automatically save the history of drafts, and to protect shared documents with passwords requires integration with a cloud service. Finally, as with any educational software, there is a learning curve for teachers and students involved, especially for lower year levels. All this suggests that the appeal of Book Creator as a literacy resource will depend on the IT environment of the school, and the intention of the class teacher to use the app for multiple projects and across multiple KLAs.

Conclusion

Book Creator for iPad is a literacy resource with the potential to transform traditional writing activities. It designed to enable primary school children to create and share multimodal texts in the form of ebooks and videos. Book Creator can be compared to a digital scrapbook, or a white canvas that can be employed across a range of teaching and learning activities. While primarily useful in supporting top-down and critical literacy approaches, it can also make bottom-up skill development activities more engaging, and support emerging readers and EAL/D learners through scaffolding functionality like text-to-speech. Book Creator is a powerful resource to teach receptive and productive language macroskills. While supporting the creative integration of all forms of media, it remains rooted in the traditional format of a book, thereby emphasising the writing and reading modalities above all others. The app becomes a transformative resource if it is integrated into a broader app environment including cloud services. This aspect, as well as the initial purchase price and the learning curve involved for teachers and students to master the app, make Book Creator a more attractive literacy resource for the sustained use across multiple key learning areas, as opposed to a resources for a single teaching and learning activity.

References

Continue reading →

Loading...

Loading...